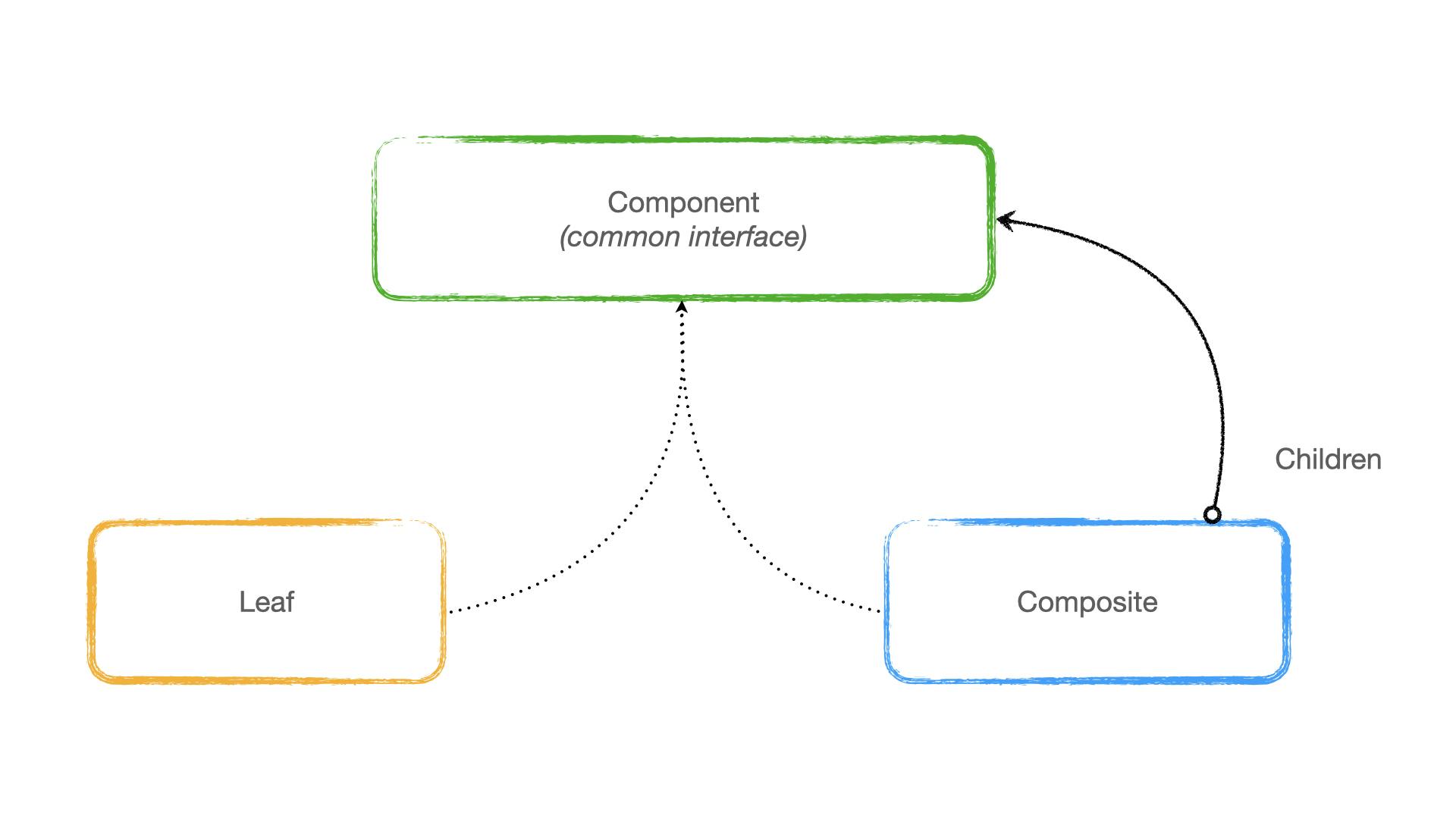

The composite design pattern allows us to create a tree structure of objects. The key idea with the pattern is that given a root component, we can access all nodes in the structure. Such access is granted using a common interface that refers to either of two object types:

Leaf - a primitive object

Composite - a group of component objects

We (mostly) do not care which underlying object type the interface is representing but we can always find out if need be (see bonus example section). As shown in the diagram above, the component is the common interface for accessing the structure. A composite stores instances of child components -- either leaves or other composites.

With the composite pattern, you only need a reference to the root component and with it, you have access to the rest of the tree. Let us look at an implementation of this pattern in Android.

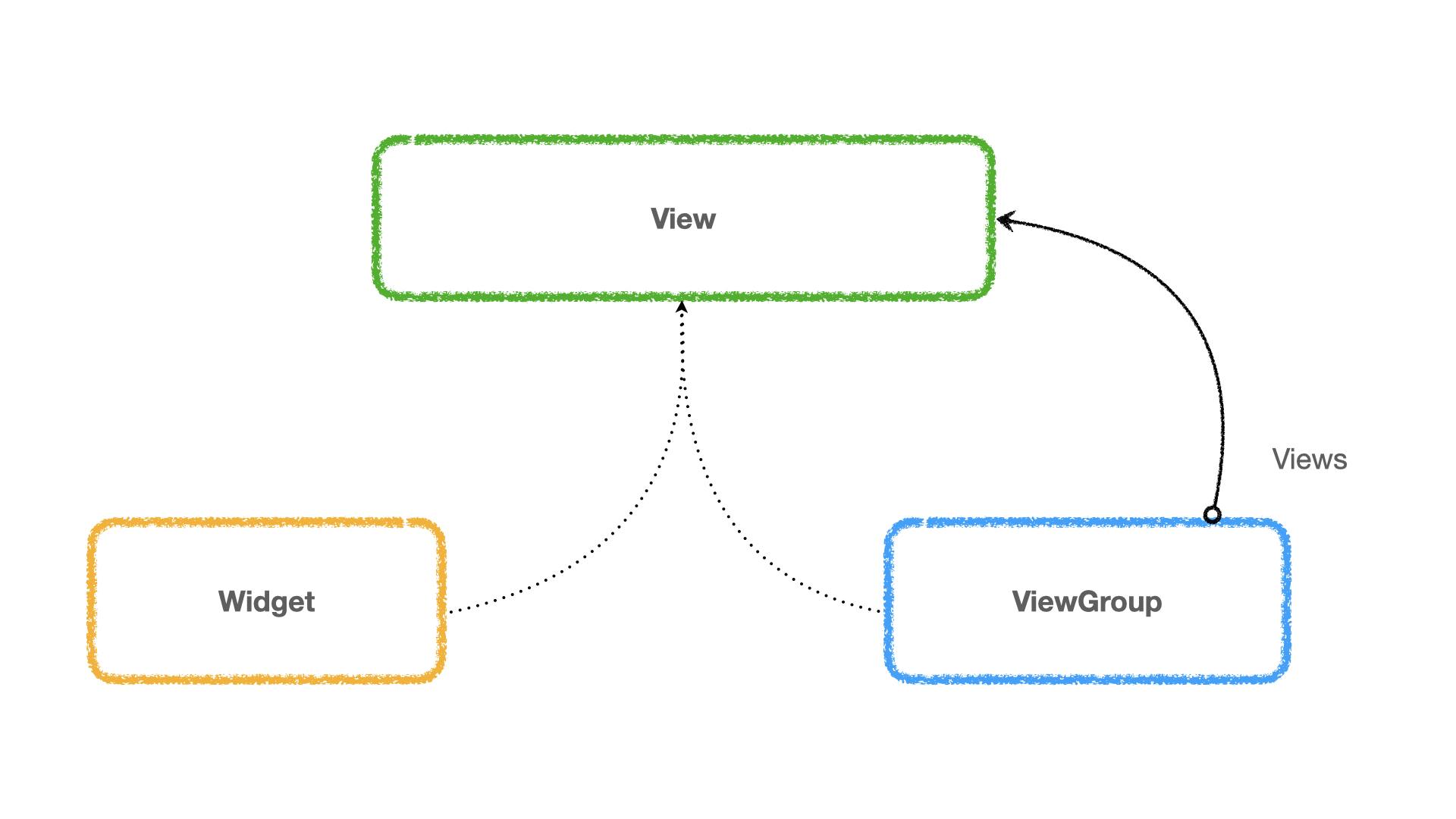

The Android View(Group)

From the Android docs on View and ViewGroup, we derive a visualization similar to the one above:

Viewis the base class for building UI elements (the component)A widget is a view representing an interactive UI component (a leaf)

A

Viewgroupis a view representing a container component to hold otherViews (the composite)

We use the relationship described here to create rich Android UIs, comprised of a hierarchy of Views. A subtle but important consequence is that each layout is referenced through a single View instance i.e. the root node of the view tree structure. The Activity class provides a setContentView api that accepts a root View instance for representing its UI.

class TheActivity : AppCompatActivity() {

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

// Some inflated view e.g. using viewbinding

val rootView: View = ...

setContentView(rootView)

}

}

The View argument to the setContentView method could be representing a one-button UI or a whole suite of widget combinations in a UI hierarchy. All the Activity requires is a reference to the root of the view hierarchy.

Consider two xml-based layouts. One has a TextView as the only view component in the layout and the other, a ConstraintLayout (a ViewGroup) that contains a TextView. Inflating each of these layouts in an Activity, we visually get the same UI.

<!-- activity_ui_with_single_widget.xml -->

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<TextView xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"

android:id="@+id/textView"

android:layout_width="match_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:gravity="center"

android:text="@string/app_name"

android:textSize="@dimen/textSize"

tools:context=".MainActivity" />

<!-- activity_ui_with_viewgroup -->

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<androidx.constraintlayout.widget.ConstraintLayout xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

xmlns:app="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res-auto"

xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"

android:id="@+id/container"

android:layout_width="match_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"

tools:context=".MainActivity">

<TextView

android:id="@+id/textView"

android:layout_width="match_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:text="@string/app_name"

android:textSize="@dimen/textSize"

android:gravity="center"

app:layout_constraintBottom_toBottomOf="parent"

app:layout_constraintLeft_toLeftOf="parent"

app:layout_constraintRight_toRightOf="parent"

app:layout_constraintTop_toTopOf="parent" />

</androidx.constraintlayout.widget.ConstraintLayout>

To render a UI on the screen, the Android framework invokes methods in the View class such as onMeasure and onDraw. These invocations are then dispatched accordingly to all nodes in the tree structure; either to a Widget or a ViewGroup. This is the composite design pattern in use.

A bonus example

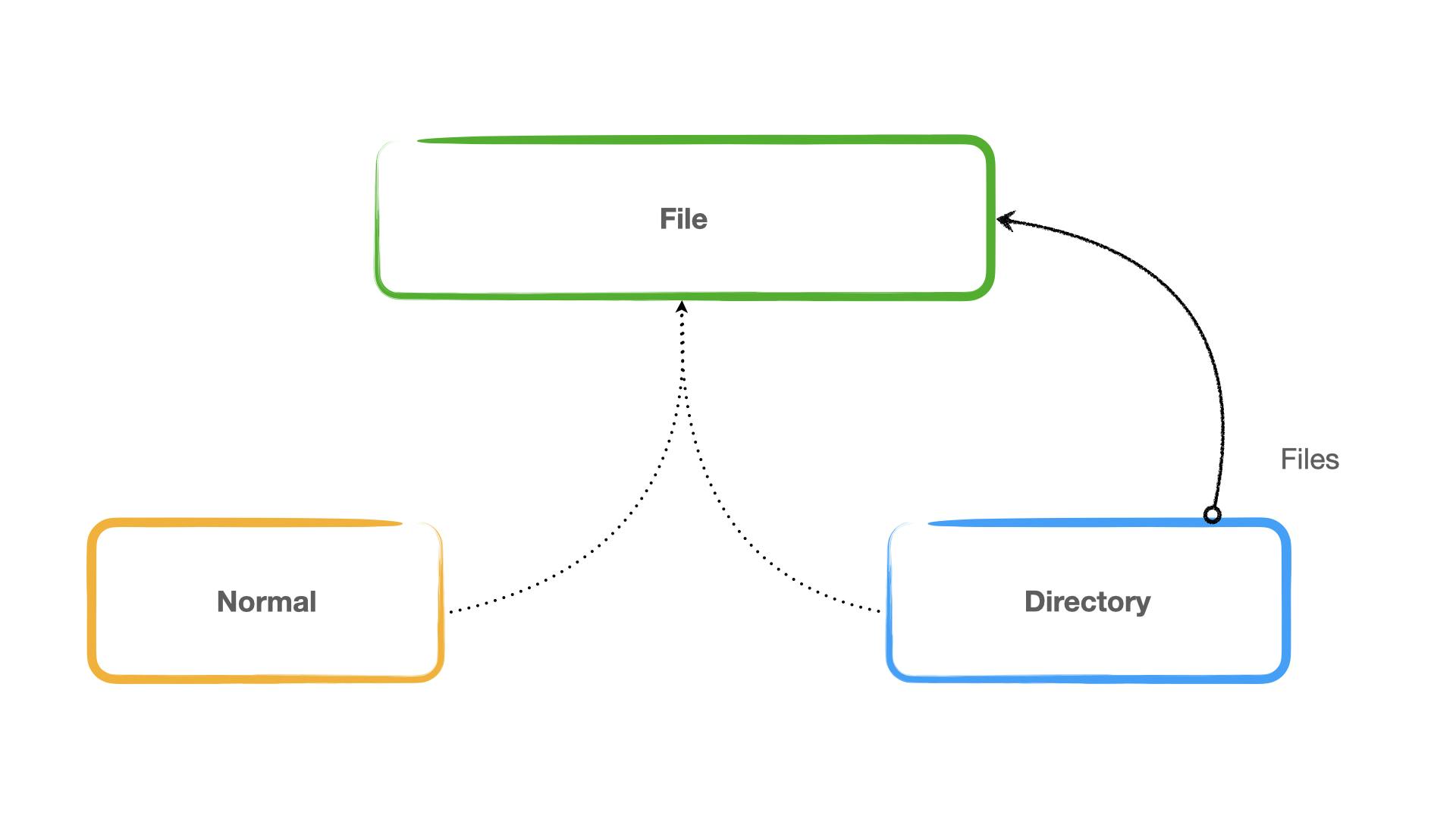

For a bonus example of the composite pattern, let's model a hypothetical representation for a filesystem. (You can find a more robust design in the Java IO package)

A file in our design can be represented as follows:

sealed interface File {

val name: String

}

File is the common interface as laid out in the pattern. We'll keep this interface simple by ignoring other typical file attributes e.g. permissions, extension etc.

For the basic filesystem elements, our design allows for two types of files - a normal and a directory file.

class Normal(override val name: String) : File

class Directory(

override val name: String,

private val files: MutableList<File> = mutableListOf()

) : File, MutableCollection<File> by files

A normal file's definition is trivial, overriding the required name property as a constructor parameter to conform to the File contract.

The directory file is a tad bit involved but conveniently expressible using Kotlin. We start by overriding the required name property as a constructor parameter. Since a directory is a mutable collection of other Files, we model it using the MutableCollection interface and delegate the collection's implementation to a MutableList instance. The list instance also facilitates the actual storage of File entries.

The relationship for File, Normal and Directory can be viewed as follows:

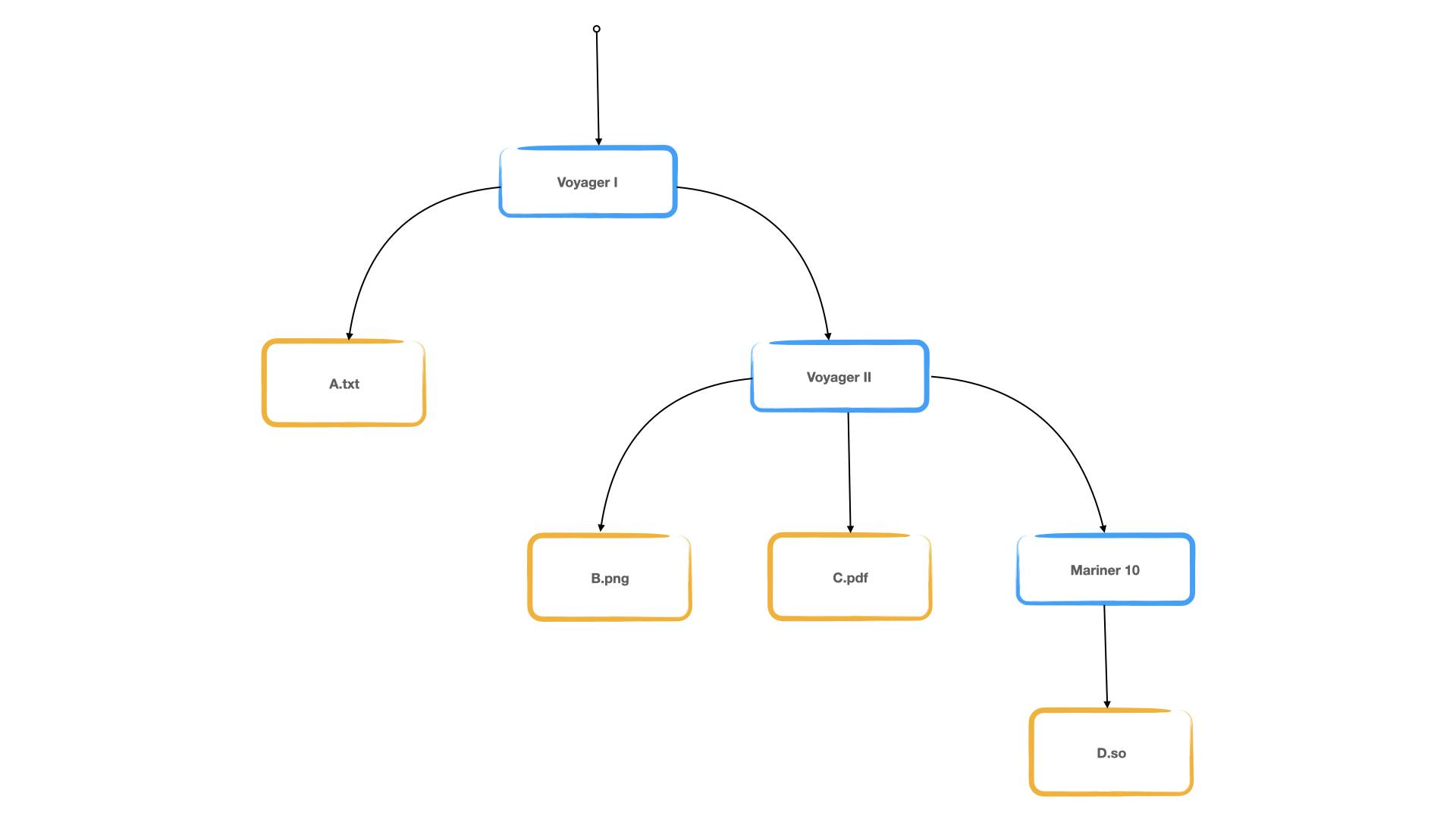

If we are tasked with printing all files for a sample filesystem shown below, our use of the composite design makes it straightforward.

Given a starting directory, here's a typical walk implementation:

fun walk(file: File, printer: Printer) {

if (file !is Directory) return // runtime-type-check

for (child in file) {

printer.print(child)

walk(child, printer)

}

}

The walk method takes as arguments a File instance and a Printer. In Kotlin, we can check the type represented by a File instance at runtime using the is operator. This allows for an early return in the method by ignoring Normal files during a recursion as they are not iterable. Each child file in a directory is then printed and then we recurse. Can you work out the output of this algorithm?

fun interface Printer {

fun print(file: File)

}

Using the File type for our printing method, as shown above, we can print any File instance - whether a normal or directory file - as Liskov Substitution principle applies. Therefore, given a root directory file, we get access to all files in the tree structure thanks to the composite pattern.

Conclusion

The composite design pattern is useful for modeling a tree structure where individual objects and composites are treated uniformly. Given a handle to the root node, you can act on all nodes in the structure. This pattern occurs time and again in written software and is a good addition to your software architecture toolbelt.

Happy coding!

Thanks, Ali for your review and suggestions.